Thirty Years' War

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Thirty Years' War was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history. The war was fought primarily (though not exclusively) in what is now Germany and at various points involved most of the countries of Europe. Naval warfare also reached overseas and shaped the colonial formation of future nations.

The origins of the conflict and goals of the participants were complex and no single cause can accurately be described as the main reason for the fighting. Initially the war was fought largely as a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire, although disputes over the internal politics and balance of power within the Empire played a significant part. Gradually, the war developed into a more general conflict involving most of the European powers.[9][10] In this general phase, the war became more a continuation of the Bourbon-Habsburg rivalry for European political pre-eminence, and in turn led to further warfare between France and the Habsburg powers, and less specifically about religion.[11]

A major impact of the Thirty Years' War was the extensive destruction of entire regions, denuded by the foraging armies (bellum se ipsum alet). Episodes of famine and disease significantly decreased the populace of the German states, Bohemia, the Low Countries and Italy, while bankrupting most of the combatant powers. While the regiments within each army were not strictly mercenary in that they were not guns for hire that changed sides from battle to battle, the individual soldiers that made up the regiments for the most part probably were. The problem of discipline was made more difficult still by the ad hoc nature of 17th century military financing. Armies were expected to be largely self-funding from loot taken or tribute extorted from the settlements where they operated. This encouraged a form of lawlessness that imposed often severe hardship on inhabitants of the occupied territory. Some of the quarrels that provoked the war went unresolved for a much longer time. The Thirty Years' War was ended with the treaties of Osnabrück and Münster, part of the wider Peace of Westphalia.[12]

Contents |

Origins of the War

The Peace of Augsburg (1555), signed by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, confirmed the result of the 1526 Diet of Speyer, ending war between German Lutherans and Catholics.[13]

- Rulers of the 225 German states could choose the religion (Lutheranism or Catholicism) of their realms according to their consciences, and compel their subjects to follow that faith (the principle of cuius regio, eius religio).

- Lutherans living in a prince-bishopric (a state ruled by a Catholic bishop) could continue to practice their faith.

- Lutherans could keep the territory that they had captured from the Catholic Church since the Peace of Passau in 1552.

- Those prince-bishops who had converted to Lutheranism were required to give up their territories (the principle called reservatum ecclesiasticum).

Although the Peace of Augsburg created a temporary end to hostilities, it did not solve the underlying religious conflict. In addition, Calvinism spread quickly throughout Germany in the years that followed. This added a third major faith to the region, but its position was not recognized in any way by the Augsburg terms, to which only Catholicism and Lutheranism were parties.[14][15]

The rulers of the nations neighboring the Holy Roman Empire also contributed to the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War:

- Spain was interested in the German states because it held the territories of the Spanish Netherlands on the western border of the Empire and states within Italy which were connected by land through the Spanish Road. The Dutch revolted against the Spanish domination during the 1560s, leading to a protracted war of independence that led to a truce only in 1609.

- France was nearly surrounded by territory controlled by the two Habsburg states (Spain and the Holy Roman Empire), and was eager to exert its power against the weaker German states; this dynastic concern overtook religious ones and led to Catholic France's participation on the otherwise Protestant side of the war.

- Sweden and Denmark were interested in gaining control over northern German states bordering the Baltic Sea.

The Holy Roman Empire was a fragmented collection of largely independent states. The position of Holy Roman Emperor was mainly titular, but the emperors, from the House of Habsburg, also directly ruled a large portion of Imperial territory (the Archduchy of Austria, as well as Bohemia and Hungary). The Austrian domain was thus a major European power in its own right, ruling over some eight million subjects. The Empire also contained several regional powers, such as Bavaria, Electoral Saxony, the Margravate of Brandenburg, the Palatinate, Hesse, the Archbishopric of Trier and Württemberg (containing from 500,000 to one million inhabitants). A vast number of minor independent duchies, free cities, abbeys, prince-bishoprics, and petty lordships (whose authority sometimes extended to no more than a single village) rounded out the Empire. Apart from Austria and perhaps Bavaria, none of those entities was capable of national-level politics; alliances between family-related states were common, due partly to the frequent practice of splitting a lord's inheritance among the various sons.

Religious tensions remained strong throughout the second half of the 16th century. The Peace of Augsburg began to unravel as some converted bishops refused to give up their bishoprics, and as certain Habsburg and other Catholic rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain sought to restore the power of Catholicism in the region. This was evident from the Cologne War (1583–88), a conflict initiated when the prince-archbishop of the city, Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg, converted to Calvinism. As he was an imperial elector, this could have produced a Protestant majority in the College that elected the Holy Roman Emperor – a position that had always been held by a Catholic.

In the Cologne War, Spanish troops expelled the former prince-archbishop and replaced him with Ernst of Bavaria, a Roman Catholic. After this success, the Catholics regained pace, and the principle of cuius regio, eius religio began to be exerted more strictly in Bavaria, Würzburg and other states. This forced Lutheran residents to choose between conversion or exile. Lutherans also witnessed the defection of the lords of the Palatinate (1560), Nassau (1578), Hesse-Kassel (1603) and Brandenburg (1613) to the new Calvinist faith. Thus at the beginning of the 17th century the Rhine lands and those south to the Danube were largely Catholic, while Lutherans predominated in the north, and Calvinists dominated in certain other areas, such as west-central Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands. However, minorities of each creed existed almost everywhere. In some lordships and cities the number of Calvinists, Catholics, and Lutherans were approximately equal.

Much to the consternation of their Spanish ruling cousins, the Habsburg emperors who followed Charles V (especially Ferdinand I and Maximilian II, but also Rudolf II, and his successor Matthias) were content for the princes of the Empire to choose their own religious policies. These rulers avoided religious wars within the empire by allowing the different Christian faiths to spread without coercion. This angered those who sought religious uniformity.[16] Meanwhile, Sweden and Denmark, both Lutheran kingdoms, sought to assist the Protestant cause in the Empire, and also wanted to gain political and economic influence there as well.

Religious tensions broke into violence in the German free city of Donauwörth in 1606. There, the Lutheran majority barred the Catholic residents of the Swabian town from holding a procession, which provoked a riot. This prompted foreign intervention by Duke Maximilian of Bavaria (1573–1651) on behalf of the Catholics. After the violence ceased, Calvinists in Germany (who remained a minority) felt the most threatened. They banded together and formed the League of Evangelical Union in 1608, under the leadership of the Palatine Prince-Elector Frederick IV (1583–1610), (whose son, Frederick V, married Elizabeth Stuart, the daughter of James I of England).[17] The establishment of the League prompted the Catholics into banding together to form the Catholic League in 1609, under the leadership of Duke Maximilian.

Tensions escalated further in 1609, with the War of the Jülich succession, which began when John William, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, the ruler of the strategically important United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, died childless.[18] There were two rival claimants to the duchy: (1) Duchess Anna of Prussia, daughter of Duke John William's eldest sister, Marie Eleonore of Cleves, and who was married to John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg; and (2) Wolfgang William, Count Palatine of Neuburg, who was the son of Duke John William's second eldest sister, Anna. Duchess Anna of Prussia claimed Jülich-Cleves-Berg as the heir to the senior line, while Wolfgang William, Count Palatine of Neuburg claimed Jülich-Cleves-Berg as Duke John William's eldest male heir. Both claimants were Protestants. In 1610, to prevent war between the rival claimants, the forces of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor occupied Jülich-Cleves-Berg until the dispute was decided by the Aulic Council (Reichshofrat). However, several Protestant princes feared that the Emperor, a devout Catholic, intended to keep Jülich-Cleves-Berg for himself in order to prevent the United Duchies falling into Protestant hands.[18] Representatives of Henry IV of France and the Dutch Republic gathered forces to invade Jülich-Cleves-Berg, but these plans were cut short by the assassination of Henry IV. Hoping to gain an advantage in the dispute, Wolfgang William, Count Palatine of Neuburg converted to Catholicism; John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, on the other hand converted to Calvinism (although Duchess Anna of Prussia stayed Lutheran).[18] The dispute was settled in 1614 with the Treaty of Xanten, by which the United Duchies were dismantled: Jülich and Berg were awarded to Wolfgang William, while the Elector of Brandenburg gained Cleves, Mark, and Ravensberg.[18]

The background of the Dutch Revolt is also necessary to understanding the events leading up to the Thirty Years War. It was widely known that the Twelve Years' Truce was set to expire in 1621, and throughout Europe it was recognized that at that time, Spain would attempt to reconquer the Dutch Republic. At that time, forces under Ambrogio Spinola, 1st Marquis of the Balbases, the Genoese commander of the Spanish army, would be able to pass through friendly territories in order to reach the Dutch Republic; the only hostile state that stood in his way was the Electoral Palatinate.[19] (Spinola's preferred route would take him through the Republic of Genoa, the Duchy of Milan, through the Val Telline, around hostile Switzerland by passing along the north shore of Lake Constance then through Alsace, the Archbishopric of Strasbourg, then through the Electoral Palatinate, and then finally through the Archbishopric of Trier, Jülich and Berg and on to the Dutch Republic).[19] The Electoral Palatinate thus assumed a strategic importance in European affairs out of all proportion to its size. This explains why the Protestant James I of England arranged for the marriage of his daughter Elizabeth Stuart to Frederick V, Elector Palatine in 1612, in spite of the social convention that a princess would only marry another royal.

By 1617 it was apparent that Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, would die without an heir, with his lands going to his nearest male relative, his cousin Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria, heir-apparent and Crown Prince of Bohemia. With the Oñate treaty, Philip III of Spain agreed to this succession.

Ferdinand, having been educated by the Jesuits, was a staunch Catholic who wanted to impose religious uniformity on his lands. This made him highly unpopular in Protestant (primarily Hussite) Bohemia. The population's sentiments notwithstanding, the added insult of the nobility's rejection of Ferdinand, who had been elected Bohemian Crown Prince in 1617, triggered the Thirty Years' War in 1618 when his representatives were thrown out of a window into a pile of horse manure. The so-called Defenestration of Prague provoked open revolt in Bohemia which had powerful foreign allies. Ferdinand was quite upset by this calculated insult, but his intolerant policies in his own lands had left him in a weak position. The Habsburg cause in the next couple of years would seem to suffer unrecoverable reverses. The Protestant cause seemed to wax toward a quick overall victory.

Phases

The war can be divided into four major phases: The Bohemian Revolt, the Danish intervention, the Swedish intervention and the French intervention.

The Bohemian Revolt

1618–1621

Without heirs, Emperor Matthias sought to assure an orderly transition during his lifetime by having his dynastic heir (the fiercely Catholic Ferdinand of Styria, later Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor) elected to the separate royal thrones of Bohemia and Hungary.[20] Some of the Protestant leaders of Bohemia feared they would be losing the religious rights granted to them by Emperor Rudolf II in his Letter of Majesty. They preferred the Protestant Frederick V, elector of the Palatinate (successor of Frederick IV, the creator of the League of Evangelical Union).[21] However, other Protestants supported the stance taken by the Catholics,[22] and in 1617, Ferdinand was duly elected by the Bohemian estates to become the Crown Prince, and automatically upon the death of Matthias, the next King of Bohemia.

The king-elect then sent two Catholic councillors (Vilem Slavata of Chlum and Jaroslav Borzita of Martinice) as his representatives to Hradčany castle in Prague in May 1618. Ferdinand had wanted them to administer the government in his absence. According to legend, the Bohemian Hussites suddenly seized them, subjected them to a mock trial, and threw them out of the palace window, which was some 50 feet off the ground. Remarkably, they survived unharmed.

This event, known as the (Second) Defenestration of Prague, started the Bohemian Revolt. Soon afterward the Bohemian conflict spread through all of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown, including Bohemia, Silesia, Lusatia, and Moravia. Moravia was already embroiled in a conflict between Catholics and Protestants. The religious conflict eventually spread across the whole continent of Europe, involving France, Sweden, and a number of other countries.[21]

Had the Bohemian rebellion remained a local conflict, the war could have been over in fewer than thirty months. However, the death of Emperor Matthias emboldened the rebellious Protestant leaders, who had been on the verge of a settlement. The weaknesses of both Ferdinand (now officially on the throne after the death of Emperor Matthias) and of the Bohemians themselves led to the spread of the war to western Germany. Ferdinand was compelled to call on his nephew, King Philip IV of Spain, for assistance.

The Bohemians, desperate for allies against the Emperor, applied to be admitted into the Protestant Union, which was led by their original candidate for the Bohemian throne, the Calvinist Frederick V, Elector Palatine. The Bohemians hinted that Frederick would become King of Bohemia if he allowed them to join the Union and come under its protection. However, similar offers were made by other members of the Bohemian Estates to the Duke of Savoy, the Elector of Saxony, and the Prince of Transylvania. The Austrians, who seemed to have intercepted every letter leaving Prague, made these duplicities public.[23] This unraveled much of the support for the Bohemians, particularly in the court of Saxony. The rebellion initially favoured the Bohemians. They were joined in the revolt by much of Upper Austria, whose nobility was then chiefly Lutheran and Calvinist. Lower Austria revolted soon after and in 1619, Count Thurn led an army to the walls of Vienna itself.

Ottoman support

In the east, the Protestant Hungarian Prince of Transylvania, Bethlen Gabor, led a spirited campaign into Hungary with the support of the Ottoman Sultan, Osman II. Fearful of the Catholic policies of Ferdinand II, Bethlen Gabor requested a protectorate by Osman, so that "the Ottoman Empire became the one and only ally of great-power status which the rebellious Bohemian states could muster after they had shaken off Habsburg rule and had elected Frederick V as a protestant king".[24] Ambassadors were exchanged, with Heinrich Bitter visiting Constantinople in January 1620, and Mehmed Aga visiting Prague in July 1620. The Ottomans offered a force of 60,000 cavalry to Frederick and plans were made for an invasion of Poland with 400,000 troops in exchange for the payment of an annual tribute to the Sultan.[25] These negotiations triggered the Polish–Ottoman War of 1620-21.[26] The Ottomans defeated the Poles, who were supporting the Habsburgs in the Thirty Years' War, at the Battle of Cecora in September-October 1620,[27] but were not able to further intervene efficiently before the Bohemian defeat at the Battle of the White Mountain in November 1620.[28]

The emperor, who had been preoccupied with the Uskok War, hurried to reform an army to stop the Bohemians and their allies from overwhelming his country. Count Bucquoy, the commander of the Imperial army, defeated the forces of the Protestant Union led by Count Mansfeld at the Battle of Sablat, on 10 June 1619. This cut off Count Thurn's communications with Prague, and he was forced to abandon his siege of Vienna. The Battle of Sablat also cost the Protestants an important ally — Savoy, long an opponent of Habsburg expansion. Savoy had already sent considerable sums of money to the Protestants and even troops to garrison fortresses in the Rhineland. The capture of Mansfeld's field chancery revealed the Savoyards' involvement and they were forced to bow out of the war.

In spite of Sablat, Count Thurn's army continued to exist as an effective force, and Mansfeld managed to reform his army further north in Bohemia. The Estates of Upper and Lower Austria, still in revolt, signed an alliance with the Bohemians in early August. On 17 August 1619 Ferdinand was officially deposed as King of Bohemia and was replaced by the Palatine Elector Frederick V. In Hungary, even though the Bohemians had reneged on their offer of their crown, the Transylvanians continued to make surprising progress. They succeeded in driving the Emperor's armies from that country by 1620.

1621–1625

The Spanish sent an army from Brussels under Ambrosio Spinola to support the Emperor. In addition, the Spanish ambassador to Vienna, Don Íñigo Vélez de Oñate, persuaded Protestant Saxony to intervene against Bohemia in exchange for control over Lusatia. The Saxons invaded, and the Spanish army in the west prevented the Protestant Union's forces from assisting. Oñate conspired to transfer the electoral title from the Palatinate to the Duke of Bavaria in exchange for his support and that of the Catholic League.

Under the command of General Philyaw, the Catholic League's army (which included René Descartes in its ranks) pacified Upper Austria, while the Emperor's forces pacified Lower Austria. The two armies united and moved north into Bohemia. Ferdinand II decisively defeated Frederick V at the Battle of White Mountain, near Prague, on 8 November 1620. In addition to becoming Catholic, Bohemia would remain in Habsburg hands for nearly three hundred years.

This defeat led to the dissolution of the League of Evangelical Union and the loss of Frederick V's holdings. Frederick was outlawed from the Holy Roman Empire and his territories, the Rhenish Palatinate, were given to Catholic nobles. His title of elector of the Palatinate was given to his distant cousin Duke Maximilian of Bavaria. Frederick, now landless, made himself a prominent exile abroad and tried to curry support for his cause in Sweden, Netherlands and Denmark.

This was a serious blow to Protestant ambitions in the region. As the rebellion collapsed, the widespread confiscation of property and suppression of the Bohemian nobility ensured that the country would return to the Catholic side after more than two centuries of Hussite and other religious dissent. The Spanish, seeking to outflank the Dutch in preparation for renewal of the Eighty Years' War, took Frederick's lands, the Rhine Palatinate. The first phase of the war in eastern Germany ended 31 December 1621, when the Prince of Transylvania and the Emperor signed the Peace of Nikolsburg, which gave Transylvania a number of territories in Royal Hungary.

Some historians regard the period from 1621–1625 as a distinct portion of the Thirty Years' War, calling it the "Palatinate phase". With the catastrophic defeat of the Protestant army at White Mountain and the departure of the Prince of Transylvania, greater Bohemia was pacified. However, the war in the Palatinate continued: Famous mercenary leaders - such as, particularly, Count Ernst von Mansfeld - helped Frederick V to defend his countries, the Upper and the Rhine Palatinate. This phase of the war consisted of much smaller battles, mostly sieges conducted by the Spanish army. Mannheim and Heidelberg fell in 1622, and Frankenthal was taken two years later, thus leaving the Palatinate in the hands of the Spanish.

The remnants of the Protestant armies, led by Count Ernst von Mansfeld and Duke Christian of Brunswick, withdrew into Dutch service. Although their arrival in the Netherlands did help to lift the siege of Bergen-op-Zoom (October 1622), the Dutch could not provide permanent shelter for them. They were paid off and sent to occupy neighboring East Friesland. Mansfeld remained in the Dutch Republic, but Christian wandered off to "assist" his kin in the Lower Saxon Circle, attracting the attentions of Tilly. With the news that Mansfeld would not be supporting him, Christian's army began a steady retreat toward the safety of the Dutch border. On 6 August 1623, Tilly's more disciplined army caught up with them 10 miles short of the Dutch border. The battle that ensued was known as the Battle of Stadtlohn. In this battle Tilly decisively defeated Christian, wiping out over four-fifths of his army, which had been some 15,000 strong. After this catastrophe, Frederick V, already in exile in The Hague, and under growing pressure from his father-in-law James I to end his involvement in the war, was forced to abandon any hope of launching further campaigns. The Protestant rebellion had been crushed.

Huguenot rebellions (1620-1628)

In France, the Protestant Huguenots, mainly located in the southwestern provinces, revolted against the central Royal power of the French government. The uprising followed the death of Henry IV, who, himself originally a Huguenot before converting to Catholicism, had protected Protestants through the Edict of Nantes. The new ruler however, Louis XIII, under the regency of his Italian Catholic mother Marie de' Medici, became more intolerant of the Protestant religion. The Huguenots tried to respond by defending themselves, establishing independent political and military structures, establishing diplomatic contacts with foreign powers, and openly revolting against central power. The Huguenot rebellions came after two decades of internal peace under Henry IV, following the intermittent French Wars of Religion of 1562–1598. The rebellion led to major military encounters, which ended in defeat for the Huguenots: the Siege of Montauban, the Naval battle of Saint-Martin-de-Ré on 27 October 1622, the Capture of Ré island in 1625, and the Siege of La Rochelle in 1627-1628 which became an international conflict with the involvement of England in the Anglo-French War (1627-1629). The House of Stuart in England had been involved in attempts to secure peace in Europe (through the Spanish Match) and had intervened in the 30 Years' War against both Spain and France. However, due in part to the scale of the defeat (which indirectly lead to the assassination of the English leader the Duke of Buckingham), and also due to the lack of funds for war, which stemmed from internal conflict between Charles I and his Parliament, England stopped being involved in European affairs, to the dismay of Protestant forces on the continent.[29] France remained the largest Catholic kingdom that was not only not aligned with the Habsburg powers but would come to actively wage war against Spain. The French Crown's response to the Hugeunot rebellion was not so much a representation of the typical religious polarisation of the Thirty Years' War, but rather the attempts at achieving national hegemony by absolutist monarchy.

Danish intervention (1625–1629)

Peace in the Empire was short-lived, however, as conflict resumed at the initiation of Denmark. Danish involvement, referred to as Low Saxon War or Kejserkrigen ("Emperor's War"),[30] began when Christian IV of Denmark, a Lutheran who was also the Duke of Holstein, a duchy within the Holy Roman Empire, helped the Lutheran rulers of neighbouring Lower Saxony by leading an army against the Imperial forces.[31] Denmark had feared that its sovereignty as a Protestant nation was threatened by the recent Catholic successes. Christian IV had also profited greatly from his policies in northern Germany. For instance, in 1621, Hamburg had been forced to accept Danish sovereignty and Christian's second son was made bishop of Bremen. Christian IV had obtained for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe. This stability and wealth was paid for by tolls on the Oresund and also by extensive war reparations from Sweden. Denmark's cause was aided by France which, together with England, had agreed to help subsidize the war. Christian had himself appointed war leader of the Lower Saxon Circle and raised an army of 20,000 mercenaries and a national army 15,000 strong.

To fight him, Ferdinand II employed the military help of Albrecht von Wallenstein, a Bohemian nobleman who had made himself rich from the confiscated estates of his countrymen.[32] Wallenstein pledged his army, which numbered between 30,000 and 100,000 soldiers, to Ferdinand II in return for the right to plunder the captured territories. Christian, who knew nothing of Wallenstein's forces when he invaded, was forced to retire before the combined forces of Wallenstein and Tilly. Christian's poor luck was with him again when all of the allies he thought he had were forced aside: England was weak and internally divided, France was in the midst of a civil war, Sweden was at war with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and neither Brandenburg nor Saxony were interested in changes to the tenuous peace in eastern Germany. Wallenstein defeated Mansfeld's army at the Battle of Dessau Bridge (1626) and General Tilly defeated the Danes at the Battle of Lutter (1626).[33] Mansfeld died some months later of illness, apparently tuberculosis, in Dalmatia.

Wallenstein's army marched north, occupying Mecklenburg, Pomerania, and ultimately Jutland itself. However, he was unable to take the Danish capital on the island of Zealand. Wallenstein lacked a fleet, and neither the Hanseatic ports nor the Poles would allow an Imperial fleet to be built on the Baltic coast. He then laid siege to Stralsund, the only belligerent Baltic port with the facilities to build a large fleet. However, the cost of continuing the war was exorbitant compared to what could possibly be gained from conquering the rest of Denmark.[34] Wallenstein feared to lose his North German gains to a Danish-Swedish alliance, and Christian IV had suffered another defeat in the Battle of Wolgast, so both were ready to negotiate.[35]

Negotiations were concluded with the Treaty of Lübeck in 1629, which stated that Christian IV could keep his control over Denmark if he would abandon his support for the Protestant German states. Thus, in the following two years more land was subjugated by the Catholic powers. At this point, the Catholic League persuaded Ferdinand II to take back the Lutheran holdings that were, according to the Peace of Augsburg, rightfully the possession of the Catholic Church. Enumerated in the Edict of Restitution (1629), these possessions included two Archbishoprics, sixteen bishoprics, and hundreds of monasteries. The same year, Gabriel Bethlen, the Calvinist Prince of Transylvania, died. Only the port of Stralsund continued to hold out against Wallenstein and the Emperor.

Swedish intervention (1630–1635)

Some within Ferdinand II's court did not trust Wallenstein, believing that he sought to join forces with the German Princes and thus gain influence over the Emperor. Ferdinand II dismissed Wallenstein in 1630. He was to later recall him after the Swedes, led by King Gustaf II Adolf (Gustavus Adolphus), had invaded the Holy Roman Empire with success and turned the tables on the Catholics. His contributions made Sweden the continental leader of Protestantism until the Swedish Empire ended in 1721.[36] [37]

Gustavus Adolphus, like Christian IV before him, came to aid the German Lutherans, to forestall Catholic aggression against their homeland, and to obtain economic influence in the German states around the Baltic Sea. In addition, Gustavus was concerned about the growing power of the Holy Roman Empire. No one knows the exact reason for Gustavus to enter the war and this has been widely argued. Like Christian IV, Gustavus Adolphus was subsidized by Cardinal Richelieu, the Chief Minister of Louis XIII of France, and by the Dutch.[38] From 1630 to 1634, Swedish-led armies drove the Catholic forces back, regaining much of the lost Protestant territory. During his campaign he managed to conquer half of the Imperial kingdoms.

Swedish forces entered the Holy Roman Empire via the Duchy of Pomerania, which served as the Swedish bridgehead since the Treaty of Stettin (1630). After dismissing Wallenstein in 1630, Ferdinand II became dependent on the Catholic League. Gustavus Adolphus allied with France in the Treaty of Bärwalde (January 1631). France and Bavaria signed the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau (1631), but this was rendered irrelevant by Swedish attacks against Bavaria. At the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631), Gustavus Adolphus's forces defeated the Catholic League led by General Tilly.[39] [40] A year later they met again in another Protestant victory, this time accompanied by the death of Tilly. The upper hand had now switched from the league to the union, led by Sweden. In 1630, Sweden had paid at least 2,368,022 daler for its army of 42,000 men. In 1632, it contributed only one-fifth of that (476,439 daler) towards the cost of an army more than three times as large (149,000 men). This was possible due to subsidies from France, and the recruitment of prisoners (most of them taken at the Battle of Breitenfeld) into the Swedish army. The majority of mercenaries recruited by Gustavus II Adolphus were German[41] but Scottish mercenaries were also common. With Tilly dead, Ferdinand II returned to the aid of Wallenstein and his large army. Wallenstein marched up to the south, threatening Gustavus Adolphus's supply chain. Gustavus Adolphus knew that Wallenstein was waiting for the attack and was prepared, but found no other option. Wallenstein and Gustavus Adolphus clashed in the Battle of Lützen (1632), where the Swedes prevailed, but Gustavus Adolphus was killed.

Ferdinand II's suspicion of Wallenstein resumed in 1633, when Wallenstein attempted to arbitrate the differences between the Catholic and Protestant sides. Ferdinand II may have feared that Wallenstein would switch sides, and arranged for his arrest after removing him from command. One of Wallenstein's soldiers, Captain Devereux, killed him when he attempted to contact the Swedes in the town hall of Eger (Cheb) on 25 February 1634. The same year, the Protestant forces, lacking Gustav's leadership, were defeated at the First Battle of Nördlingen by the Spanish-Imperial forces commanded by Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand.

By the Spring of 1635, all Swedish resistance in the south of Germany had ended. After that, the two sides met for negotiations, producing the Peace of Prague (1635), which entailed a delay in the enforcement of the Edict of Restitution for 40 years and allowed Protestant rulers to retain secularized bishoprics held by them in 1627. This protected the Lutheran rulers of northeastern Germany, but not those of the south and west (whose lands had been occupied by the Imperial or League armies prior to 1627).

The treaty also provided for the union of the army of the Emperor and the armies of the German states into a single army of the Holy Roman Empire (although Johann Georg of Saxony and Maximillian of Bavaria kept, as a practical matter, independent command of their forces, now nominally components of the "Imperial" army). Finally, German princes were forbidden from establishing alliances amongst themselves or with foreign powers, and amnesty was granted to any ruler who had taken up arms against the Emperor after the arrival of the Swedes in 1630.

This treaty failed to satisfy France, however, because of the renewed strength it granted the Habsburgs. France then entered the conflict, beginning the final period of the Thirty Years' War.

French intervention (1635–1648)

.jpg)

France, although Roman Catholic, was a rival of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. Cardinal Richelieu, the Chief Minister of King Louis XIII of France, felt that the Habsburgs were too powerful, since they held a number of territories on France's eastern border, including portions of the Netherlands. Richelieu had already begun intervening indirectly in the war in January 1631, when the French diplomat Hercules de Charnace signed the Treaty of Bärwalde with Gustavus Adolphus, by which France agreed to support the Swedes with 1,000,000 livres each year in return for a Swedish promise to maintain an army in Germany against the Habsburgs. The treaty also stipulated that Sweden would not conclude a peace with the Holy Roman Emperor without first receiving France's approval.

After the Swedish rout at Nördlingen in September 1634 and the Peace of Prague in 1635, as Sweden's ability to continue the war alone appeared doubtful, Richelieu made the decision to enter into direct war against the Habsburgs. France declared war on Spain in May 1635 and the Holy Roman Empire in August 1636, opening offensives against the Habsburgs in Germany and the Low Countries. France aligned her strategy with the allied Swedes in Wismar (1636) and Hamburg (1638).

French military efforts met with disaster, and the Spanish counter-attacked, invading French territory. The Imperial general Johann von Werth and Spanish commander Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Spain ravaged the French provinces of Champagne, Burgundy and Picardy, and even threatened Paris in 1636 before being repulsed by Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar. Bernhard's victory in the Battle of Compiègne pushed the Habsburg armies back towards the borders of France. Widespread fighting ensued, with neither side gaining an advantage. In 1642, Cardinal Richelieu died. A year later, Louis XIII died, leaving his five-year-old son Louis XIV on the throne. His chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, facing the domestic crisis of the Fronde in 1645, began working to end the war.

In 1643, the Swedish marshal Lennart Torstenson expelled Danish prince Frederick from Bremen-Verden, gaining a stronghold south of Denmark and hindering Danish participation as mediatiors in the peace talks in Westphalia.[42] In 1645, Torstenson defeated the Imperial army at the Battle of Jankau near Prague, and Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé defeated the Bavarian army in the Second Battle of Nördlingen. The last Catholic commander of note, Baron Franz von Mercy, died in the battle.[43]

On 14 March 1647 Bavaria, Cologne, France and Sweden signed the Truce of Ulm. In 1648 the Swedes (commanded by Marshal Carl Gustaf Wrangel) and the French (led by Turenne and Condé) defeated the Imperial army at the Battle of Zusmarshausen and Lens. These results left only the Imperial territories of Austria safely in Habsburg hands.

Peace of Westphalia

French General Louis II de Bourbon, 4th Prince de Condé, Duc d'Enghien, The Great Condé defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Rocroi in 1643, which led to negotiations. Over a four year period, the parties were actively negotiating at Osnabrück and Münster in Westphalia.[44] The end of the war was not brought about by one treaty but instead by a group of treaties such as the Treaty of Hamburg.[45] On 15 May 1648, the Treaty of Osnabrück was signed. Over five months later, on 24 October, the Treaty of Münster was signed, ending both the Thirty Years' War and the Eighty Years' War.[46][47] [48]

Casualties and disease

So great was the devastation brought about by the war that estimates put the reduction of population in the German states at about 15% to 30%.[49] Some regions were affected much more than others.[50] For example, Württemberg lost three-quarters of its population during the war.[51] In the territory of Brandenburg, the losses had amounted to half, while in some areas an estimated two-thirds of the population died.[52] The male population of the German states was reduced by almost half.[53] The population of the Czech lands declined by a third due to war, disease, famine and the expulsion of Protestant Czechs.[54][55] Much of the destruction of civilian lives and property was caused by the cruelty and greed of mercenary soldiers, many of whom were rich commanders and poor soldiers.[56] Villages were especially easy prey to the marauding armies. Those that survived, like the small village of Drais near Mainz would take almost a hundred years to recover. The Swedish armies alone may have destroyed up to 2,000 castles, 18,000 villages and 1,500 towns in Germany, one-third of all German towns.[57] The war caused serious dislocations to both the economies and populations of central Europe, but may have done no more than seriously exacerbate changes that had begun earlier.[58][59]

Pestilence of several kinds raged among combatants and civilians in Germany and surrounding lands from 1618 to 1648. Many features of the war spread disease. These included troop movements, the influx of soldiers from foreign countries, and the shifting locations of battle fronts. In addition, the displacement of civilian populations and the overcrowding of refugees into cities led to both disease and famine. Information about numerous epidemics is generally found in local chronicles, such as parish registers and tax records, that are often incomplete and may be exaggerated. The chronicles do show that epidemic disease was not a condition exclusive to war time, but was present in many parts of Germany for several decades prior to 1618.[60]

However, when the Danish and Imperial armies met in Saxony and Thuringia during 1625 and 1626, disease and infection in local communities increased. Local chronicles repeatedly referred to "head disease", "Hungarian disease", and a "spotted" disease identified as typhus. After the Mantuan War, between France and the Habsburgs in Italy, the northern half of the Italian peninsula was in the throes of a bubonic plague epidemic (see Italian Plague of 1629–1631). During the unsuccessful siege of Nuremberg, in 1632, civilians and soldiers in both the Swedish and Imperial armies succumbed to typhus and scurvy. Two years later, as the Imperial army pursued the defeated Swedes into southwest Germany, deaths from epidemics were high along the Rhine River. Bubonic plague continued to be a factor in the war. Beginning in 1634, Dresden, Munich, and smaller German communities such as Oberammergau recorded large numbers of plague casualties. In the last decades of the war, both typhus and dysentery had become endemic in Germany.

Political consequences

One result of the war was the division of Germany into many territories — all of which, despite their membership in the Empire, won de facto sovereignty. This limited the power of the Holy Roman Empire and decentralized German power.

The Thirty Years' War rearranged the European power structure. The last decade of the conflict saw clear signs of Spain weakening. While Spain was fighting in France, Portugal — which had been under personal union with Spain for 60 years — acclaimed John IV of Braganza as king in 1640, and the House of Braganza became the new dynasty of Portugal (see Portuguese Restoration War, for further information). Meanwhile, Spain was forced to accept the independence of the Dutch Republic in 1648, ending the Eighty Years' War. Bourbon France challenged Habsburg Spain's supremacy in the Franco-Spanish War (1635-59); gaining definitive ascendancy in the War of Devolution (1667-68), and the Franco-Dutch War (1672-78), under the leadership of Louis XIV.

From 1643–45, during the last years of the Thirty Years' War, Sweden and Denmark fought the Torstenson War. The result of that conflict and the conclusion of the great European war at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 helped establish post-war Sweden as a force in Europe.[45]

The edicts agreed upon during the signing of the Peace of Westphalia were instrumental in laying the foundations for what are even today considered the basic tenets of the sovereign nation-state. Aside from establishing fixed territorial boundaries for many of the countries involved in the ordeal (as well as for the newer ones created afterwards), the Peace of Westphalia changed the relationship of subjects to their rulers. In earlier times, people had tended to have overlapping political and religious loyalties. Now, it was agreed that the citizenry of a respective nation were subjected first and foremost to the laws and whims of their own respective government rather than to those of neighboring powers, be they religious or secular.

The war also has a few more subtle consequences. The Thirty Years' War marked the last major religious war in mainland Europe, ending the large-scale religious bloodshed accompanying the Reformation, in 1648. There were other religious conflicts in the years to come, but no great wars.[61] Also, the destruction caused by mercenary soldiers defied description (see Schwedentrunk). The war did much to end the age of mercenaries that had begun with the first Landsknechts, and ushered in the age of well-disciplined national armies.

The war also had consequences abroad, as the European powers extended their fight via naval power to overseas colonies. In 1630, a Dutch fleet of 70 ships had taken the rich sugar-exporting areas of Pernambuco (Brazil) from the Portuguese but had lost everything by 1654. Fighting also took place in Africa and Asia.

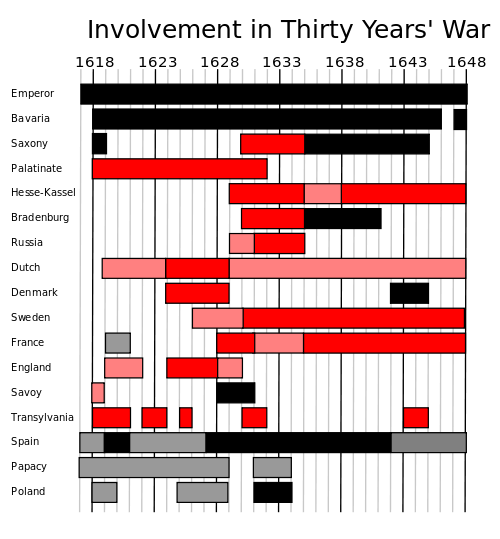

Involved states (chart)

| Directly against Emperor | |

| Indirectly against Emperor | |

| Directly for Emperor | |

| Indirectly for Emperor |

Fiction

- Vida y hechos de Estebanillo González, hombre de buen humor, compuesta por él mismo (Antwerp, 1646). The last of the great Spanish Golden Age picaresque novels, set against the background of the Thirty Years' War and thought to be authored by a writer in the entourage of Ottavio Piccolomini. The main character crisscrosses Europe at war in his role as messenger, witnessing, among other events, the 1634 battle of Nordlingen.

- Simplicius Simplicissimus (1668) by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, one of the most important German novels of the 17th century, is the comic fictional autobiography of a German peasant turned mercenary who serves under various powers during the war, based on the author's first-hand experience. An opera adaptation by the same name was produced in the 1930s, written by Karl Amadeus Hartmann.

- Daniel Defoe (1720). Memoirs of a Cavalier. "A Military Journal of the Wars in Germany, and the Wars in England. From the Years 1632 to 1648".

- George Alfred Henty (1886). Lion of the North, A Tale of Gustavus Adolphus and the Wars of Religion. From Internet Archive.

- George Alfred Henty (1900). Won by the Sword; A Tales of the Thirty Years' War, With twelve illus. by C.M. Sheldon, and four plans. From Internet Archive.

- Hermann Löns (1910). The Warwolf (Der Wehrwolf), an alternately heart-warming and heart-rending chronicle of a North German farming community suffering tragedies and ultimate triumph during the harrowing period of the Thirty Years' War.

- Edmond Rostand's play Cyrano de Bergerac (act IV is set during the siege of Arras in 1640).

- Bertolt Brecht's play Mother Courage and Her Children, an anti-war theatre piece, is set during the Thirty Years' War.

- Queen Christina, the 1933 film starring Greta Garbo, opens with the death of Christina's father, King Gustavus Adolphus, at the Battle of Lützen in the Thirty Years' War. The subsequent plot of the film is entirely set against the backdrop of the war and her determination as Queen, as depicted a decade later, to end the war and bring about peace and resolution.

- The Last Valley (1971). A film starring Michael Caine and Omar Sharif, who discover a temporary haven from the Thirty Years' War. Written by James Clavell, the author of Shogun.

- The Last Valley (1959) by J. B. Pick. The book upon which the film version was based. Originally published in Great Britain as The Fat Valley.

- Michael Moorcock's novel, The War Hound and the World's Pain (1981) has as its central character Ulrich von Bek, a mercenary who took part in the sack of Magdeburg.

- Eric Flint's Ring of Fire series of novels deals with a temporally displaced West Virginia town from the early 21st century arriving in the early 1630s war torn Germany. The experimental novel has grown into an intensive collaborative fiction online project now in its seventh year which explores how modern knowledge and the cast of 3-3,500 townies would impact the developmental history of Europe; the theme of what would occur if the Americans set a course deliberately to undermine the power of the nobility in Europe and introduce things like a Bill of Rights, Nationalism, et al. are at the heart of the works.

- Friedrich Schiller's Wallenstein trilogy (1799) is a fictional account of the downfall of this general.

- Alessandro Manzoni's I Promessi Sposi (1842) is an historical novel taking place in Italy in 1629. It treats a couple whose marriage is interrupted, among other things, by the Bubonic Plague, and other complications of 30 Years' War.

- Parts of Neal Stephenson's Baroque Cycle are set in lands devastated by the Thirty Year's War.

- Das Treffen in Telgte (1979) trans. The Meeting at Telgte (1981) by Günther Grass, set in the aftermath of the war, sets out to make implicit parallels with the postwar Germany of the late 1940s.

See also

- Second Thirty Years War

- List of wars and disasters by death toll

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1625-1629. Aligned with the Catholic Powers 1643-1645.

- ↑ George Ripley, Charles Anderson Dana, The American Cyclopaedia, New York, 1874, p. 250, "...the standard of France was white, sprinkled with golden fleur de lis...". *[1] The original Banner of France was strewn with fleurs-de-lis. *[2]:on the reverse of this plate it says: "Le pavillon royal était véritablement le drapeau national au dix-huitième siecle...Vue du chateau d'arrière d'un vaisseau de guerre de haut rang portant le pavillon royal (blanc, avec les armes de France)."[3] from the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica: "The oriflamme and the Chape de St Martin were succeeded at the end of the 16th century, when Henry III., the last of the house of Valois, came to the throne, by the white standard powdered with fleurs-de-lis. This in turn gave place to the famous tricolour." France entered the war in 1635.

- ↑ At war with Spain 1625-30 (and France 1627-29).

- ↑ Scores Hungarians was fall into line with army of Gabriel Bethlen in 1620. Ágnes Várkonyi: Age of the Reforms, Magyar Könyvklub publisher, 1999. ISBN 963 547 070 3

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica, entry National Flags: "The Austrian imperial standard has, on a yellow ground, the black double-headed eagle, on the breast and wings of which are imposed shields bearing the arms of the provinces of the empire . The flag is bordered all round, the border being composed of equal-sided triangles with their apices alternately inwards and outwards, those with their apices pointing inwards being alternately yellow and white, the others alternately scarlet and black ." Also, Whitney Smith, Flags through the ages and across the world, McGraw-Hill, England, 1975 ISBN 0-07-059093-1, pp.114 - 119, "The imperial banner was a golden yellow cloth...bearing a black eagle...The double-headed eagle was finally established by Sigismund as regent...".

- ↑ Ervin Liptai: Military history of Hungary, Zrínyi Military Publisher, 1985. ISBN 963-326-337-9

- ↑ Gabriel Bethlen's army numbered 5,000 Hungarian pikeman and 1,000 German mercenary, with the anti-Habsburg Hungarian rebels numbered together approx. 35,000 men. László Markó: The Great Honors of the Hungarian State (A Magyar Állam Főméltóságai), Magyar Könyvklub 2000. ISBN 963 547 085 1

- ↑ László Markó: The Great Honors of the Hungarian State (A Magyar Állam Főméltóságai), Magyar Könyvklub 2000. ISBN 963 547 085 1

- ↑ "The Thirty-Years-War". Western New England College. http://mars.wnec.edu/~grempel/courses/wc2/lectures/30yearswar.html. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "::The Thirty Years War 1621 to 1626:". www.historylearningsite.co.uk. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/30YW_1621-1626.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ↑ "Thirty Years' War". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9072150/Thirty-Years-War. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ Richard W. Rahn (2006-12-21). "Avoiding a Thirty Years War". The Washington Post. www.discovery.org. http://www.discovery.org/a/3859. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "Diets of Speyer (German history) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". www.britannica.com. http://www.britannica.com/eb/topic-559499/Diets-of-Speyer. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "::The Peace of Prague::". www.historylearningsite.co.uk. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/peace_of_prague.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "Peace of Prague (1635) - Historic Event — German Archive: The Peace of Prague of 30 May 1635 was a treaty between the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II, and most of the Protestant states of the Empire. It effectively brought to an end the civil war aspect of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648); however, the war still carried on due to the continued intervention on German soil of Spain, Sweden, and, from mid-1635, France.". www.germannotes.com. http://www.germannotes.com/archive/article.php?products_id=492. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "The Thirty Years War". Pipeline. http://www.pipeline.com/~cwa/TYWHome.htm#Background. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "Frederick the Winter King. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-07". www.bartleby.com. http://www.bartleby.com/65/fr/FredWK.html. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 C. V. Wedgwood, The Thirty Years War (Penguin, 1957, 1961), p. 48.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 C. V. Wedgwood, The Thirty Years War (Penguin, 1957, 1961), p. 50.

- ↑ "The Defenestration of Prague « Criticality". steveedney.wordpress.com. http://steveedney.wordpress.com/2006/05/23/the-defenestration-of-prague/. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Bohemian Revolt-30 Years War". Thirty Years War. http://thirtyyearswar.tripod.com/revolt.html. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "Wars of the Western Civilization". www.visualstatistics.net. http://www.visualstatistics.net/east-west/War%20West/War%20West.htm#Thirty. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ T. Walter Wallbank, Alastair M. Taylor, Nels M. Bailkey, George F. Jewsbury, Clyde J. Lewis, Neil J. Hackett , Bruce Borland (Ed.) (1992). Civilization Past & Present Volume II. New York, N.Y: Harper Collins Publishers. pp. 15. The Development of the European State System: 1300–1650.. ISBN 0-673-38869-7. http://history-world.org/The%20Thirty%20Years'%20War.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ↑ An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire Halil İnalcık, Suraiya Faroqhi, Donald Quataert, Bruce McGowan, Sevket Pamuk, Cambridge University Press, 1997 ISBN 0-521-57455-2 p.424-425 [4]

- ↑ The winter king Brennan C. Pursell p.112-113

- ↑ God's Playground: The origins to 1795 by Norman Davies p

- ↑ History of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey by Ezel Kural Shaw p.191 [5]

- ↑ Halil İnalcık, p.424-425

- ↑ Peltonen, p.271

- ↑ Lockhart, Paul Douglas (2007). Denmark, 1513-1660: the rise and decline of a Renaissance monarchy. Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 0199271216. http://www.google.de/books?id=TkteH2TrSSsC&pg=PA166. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Danish Kings · Christian 4.". www.danskekonger.dk. http://www.danskekonger.dk/eng/biografi/ChrIV.html. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "Wallenstein Palace Gardens". www.prague-guide.co.uk. http://www.prague-guide.co.uk/categories/Attractions,-What-to-See/Wallenstein-Palace-Gardens/. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ The Danish interval

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Albrecht von Wallenstein". www.newadvent.org. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15538b.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ *Lockhart, Paul Douglas (2007). Denmark, 1513-1660: the rise and decline of a Renaissance monarchy. Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0199271216. http://www.google.de/books?id=TkteH2TrSSsC&pg=PA170. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ↑ The Thirty-Years-War

- ↑ "Thirty Years War". www.hyperhistory.com. http://www.hyperhistory.com/online_n2/civil_n2/histscript6_n2/thirty1.html. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "Lecture 6: Europe in the Age of Religious Wars, 1560-1715". www.historyguide.org. http://www.historyguide.org/earlymod/lecture6c.html. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "HistoryNet — From the World’s Largest History Magazine Publisher » Thirty Years’ War: Battle of Breitenfeld". www.historynet.com. http://www.historynet.com/thirty-years-war-battle-of-breitenfeld.htm/6. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ and Lützen: AD 1631-1632 "History of THE THIRTY YEARS' WAR". www.historyworld.net. http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ac18#Breitenfeld and Lützen: AD 1631-1632. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ http://www.sfhm.se/templates/pages/ArmeStandardPage____1241.aspx?epslanguage=EN

- ↑ Böhme, Klaus-R (2001). "Die sicherheitspolitische Lage Schwedens nach dem Westfälischen Frieden". In Hacker, Hans-Joachim (in German). Der Westfälische Frieden von 1648: Wende in der Geschichte des Ostseeraums. Kovač. p. 35. ISBN 3830005008.

- ↑ "Franz, baron von Mercy -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". www.britannica.com. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9052107/Franz-baron-von-Mercy. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ↑ "::The Thirty Years War::". Chris Atkinson. http://www.pipeline.com/~cwa/TYWHome.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "::The Peace of Westphalia::". www.historylearningsite.co.uk. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/peace_of_westphalia.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ↑ "::The Thirty Years War::". Chris Atkinson. http://www.pipeline.com/~cwa/TYWHome.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ↑ End of the Eighty Years War "The Thirty Years War: The Peace of Westphalia". www.pipeline.com. http://www.pipeline.com/~cwa/Westphalia_Phase.htm#The End of the Eighty Years War. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ↑ "Germany History Timeline". www.countryreports.org. http://www.countryreports.org/history/timeline.aspx?countryId=91. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "The Thirty Years War (1618-48)". Twentieth Century Atlas. http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/warstat0.htm#30YrW. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ Thirty Years’ War: Battle of Breitenfeld, HistoryNet

- ↑ "Germany — The Thirty Years' War — The Peace of Westphalia". About.com. http://historymedren.about.com/library/text/bltxtgermany16.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ Prussia in the later 17th Century, University of Wisconsin-Madison

- ↑ Coins of the Thirty Years War, The Wonderful World of Coins, Journal of Antiques & Collectibles January Issue 2004

- ↑ "The Thirty Years' War — Czech republic". www.czech.cz. http://www.czech.cz/en/czech-republic/history/all-about-czech-history/the-thirty-years-war/. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "Historical/Cultural Timeline - 1600s". College of Education, University of Houston. http://www.fm.coe.uh.edu/timeline/1600s.html. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ "The Thirty Year War and its Consequences — Universitätsstadt Tübingen". www.tuebingen.de. http://www.tuebingen.de/en/1560_6209.html. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ↑ "Population". History Learningsite. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/population_thirty_years_war.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ Germany after the Thirty Years War, Boise State University

- ↑ "The Thirty Years' War". history-world.org. http://history-world.org/The%20Thirty%20Years'%20War.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ↑ War and Pestilence, Time

- ↑ "Lecture 6: Europe in the Age of Religious Wars, 1560-1715". www.historyguide.org. http://www.historyguide.org/earlymod/lecture6c.html. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

Further reading

- Åberg, A. (1973). "The Swedish army from Lützen to Narva". In Roberts, M.. Sweden’s Age of Greatness, 1632–1718. London: St. Martin's Press.

- Benecke, Gerhard (1978). Germany in the Thirty Years War. London: St. Martin's Press.

- Luca Cristini, 1618-1648 la guerra dei 30 anni . volume 1 da 1618 al 1632 2007 (ISBN 978-88-903010-1-8)

- Luca Cristini, 1618-1648 la guerra dei 30 anni . volume 2 da 1632 al 1648 2007 (ISBN 978-88-903010-2-5)

- Gindely, Antonín (1884). History of the Thirty Years' War. Putnam. http://books.google.com/?id=ZDxvj7NG_1sC.

- Gutmann, Myron P. (1988). "The Origins of the Thirty Years' War". Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18 (4): 749–770. doi:10.2307/204823. http://jstor.org/stable/204823.

- Kamen, Henry (1968). "The Economic and Social Consequences of the Thirty Years' War". Past and Present 39: 44–61. doi:10.1093/past/39.1.44.

- Kennedy, Paul (1988). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. New York: Harper Collins.

- Langer, Herbert (1980). The Thirty Year's War. Poole, England: Blandford Press.

- Murdoch, Steve (2001). Scotland and the Thirty Years' War, 1618-1648. Brill.

- Parker, Geoffrey (1984). The Thirty Years' War. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Polišenský, J. V. (1954). "The Thirty Years' War". Past and Present 6: 31–43. doi:10.1093/past/6.1.31.

- Polišenský, J. V. (1968). "The Thirty Years' War and the Crises and Revolutions of Seventeenth-Century Europe". Past and Present 39: 34–43. doi:10.1093/past/39.1.34.

- Prinzing, Friedrich (1916). Epidemics Resulting from Wars. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Roberts, Michael (1953, 1958). Gustavus Adolphus: A History of Sweden, 1611–1632.

- Ward, A. W. (1902). The Cambridge Modern History, vol 4: The Thirty Years War. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=100053841.

- Wedgwood, C.V.; Kennedy, Paul (2005). Thirty Years War. New York: The New York Review of Books, Inc.. ISBN 1590171462.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2009). Europe’s Tragedy: A History of the Thirty Years War. Allen Lane. ISBN 9780713995923.

External links

- The Thirty Years' War - Czech republic

- Thirty Years' War - LoveToKnow 1911

- The Thirty Years War - The Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Thirty Years War LearningSite

- Thirty Years War Timeline

- Project "Peace of Westphalia" (among others with Essay Volumes of the 26th Exhibition of the Council of Europe "1648: War and Peace in Europe", 1998/99)

- History of the Thirty Years' War by Friedrich von Schiller at Project Gutenberg

- The Thirty Years War

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||